The Return of the Brooch

The brooch is making a comeback, and it's in full swing. You're seeing it on coats, scarves, knits, bags, and other articles.

The brooch has proved to be gender-neutral; Zendaya at the 2025 Met Gala tastefully sported a curled diamond snake brooch on the center seam of the back of her suit. At the 2026 Golden Globes, audiences were pummelled with brooch after brooch, from the director of Wicked to Michael Jordan. Perhaps most eye-catching of all was actor Colman Domingo, who had a party of ivy-shaped diamond brooches across the lapel of his suit.

It may seem like a new fashion buzz, but the brooch is not driven by trends. The brooch is a gathering of centuries of refinement, and now, a quiet moment of intentionality.

Historical Context

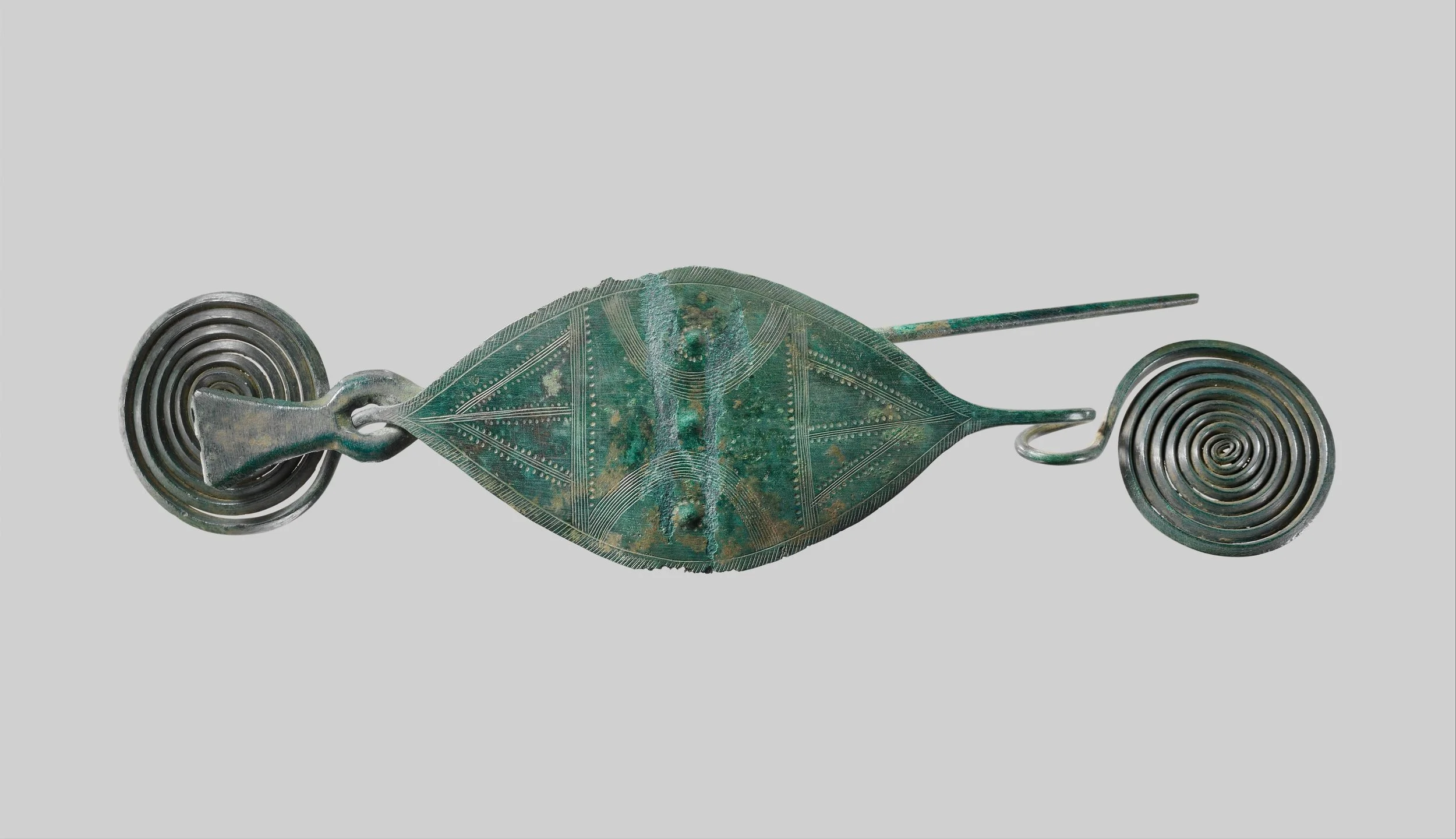

Originally considered a necessary article of clothing, the brooch wasn’t first associated with beauty but served a pragmatic purpose. In an epoch long before the zipper, adhesive glue, or sewing machine, the brooch held one’s garments together and was made of thorn or flint. These evolved into pins of wood, bronze, and metals during the Bronze Age.

A gold spiral brooch discovered and dated during this time period demonstrates a gradual transition from utilitarian values to aesthetics.

A gold spiral brooch discovered and dated during this time period demonstrates a gradual transition from utilitarian values to aesthetics.

Although the brooch’s primary function was to hold garments such as a shawl or scarf together in the Byzantine and Roman eras, its ornamental potential began to be recognized. Once made of rather simple materials, it was now fashioned with bronze, silver, and gold.

The brooch eventually became a fashion statement, symbolizing economic prosperity, with more ornate brooches paraded around by the wealthier. The Roman “crossbow fibula” became standard wear for military personnel, whereas a disk-shaped brooch was worn among civilians. The brooch distinguished, signaling power and profession.

The Etruscans and the Greeks carved intricate wirework and animal shapes on their brooches, which often had symbolic and spiritual meaning. Where before the brooch had been a practical defense against colder weather by holding garments together, it then acted as adornment and amulet.

Given Romanticism’s snubbery of reason and the Victorian fascination with family and mourning, it should come as no surprise that both eras elevated the brooch as a piece of jewelry that communicated one’s emotions and sentimentality. For instance, some brooches had a compartment for hair, in case one desired to preserve the locks of a long-ago lover. A mourning brooch’s dark enamel might also represent bereavement. One could wear their heart on their sleeve — literally.

The brooch would be thematic, almost chameleonic, in subsequent time periods, from the “en tremblant” brooch that enlightened every room prior to the invention of electricity, to the affordable love or “sweetheart” brooch that made small luxuries possible and allowed romance to flourish during WWII.

So, why the resurgence?

As fashion and other habits of the era fade, sometimes there arises an opposite sentiment.

For instance, romanticism sought to explore one’s emotions, perhaps repressed by a Neoclassicist outlook for reason.

In today’s fashion world, the minimalist mindset is now punctuated with rather maximalist statements, a swing in the opposite direction. The drab palette of beige, black, grey, and white and the “one-size fits all” facade into the background.

While supposedly more affordable and constantly serving on-trend looks, the fast fashion movement exploited labour conditions and wages for quicker production lines and impacted the environment in ways we continue to face. The emerging term for its successor, “slow fashion,” reevaluates every “fast” aspect, down to the consumer’s decision pace at purchase.

Imitating a trending look leaves less room for personal expression. It’s chasing after one look, and that look may not be yours. One commentator notes a “creative numbness” that comes from swallowing microtrend after microtrend, and the “mass-produced similarity” that results (“The Era of Sameness”). Fast-fashion sameness moves to the back of the closet for personal narrative in dress, with objects that feel inherited and intentional — like the brooch. Wearing Grandmother’s brooch is a tribute to the occasions it honored and the sentiments it conveyed, almost, perhaps, a ceremonial act.

The cultural parallel

The brooch may also be a move away from a frictionless digital life. Often, brooches make political statements, and they’re here to be seen. We return to texture, which imbues a sense of emotional attachment and freedom from a purely digital world towards something that feels more vivid. We return to weight, not only in the physical sense, but also to the history the heirloom brooch carries.

Fashion is no longer a uniform, but a means to tell a story.

Small objects, charged with symbolism and personal meaning, can say more than a head-to-toe ensemble.

Sources & Further Readinghttps://www.britannica.com/art/broochhttps://www.gia.edu/doc/Art-Deco-The-Period-the-Jewelry.pdfhttps://myjewelryrepair.com/2025/09/first-of-its-kind-the-brooch/https://www.thejewelleryeditor.com/jewellery/vintage/know-how/history-of-brooches-evolution-of-style/https://broochery.com/blogs/brooch-rachels-blog/the-history-and-evolution-of-broocheshttps://www.linkedin.com/pulse/texture-fashion-resurgence-tactile-fabrics-contemporary-noi4f/https://www.broochella.com/en-us/blogs/news/brooches-are-having-a-renaissance-and-this-is-how-we-wear-them-in-2025https://dsfantiquejewelry.com/blogs/journal/the-art-and-symbolism-of-renaissance-jewelryhttps://besque.substack.com/p/the-era-of-sameness-and-why-fashionhttps://whoworewhatjewels.com/tag/patrick-schwarzeneggers-brooches-at-2026-golden-globes/https://www.luxurylifestylemag.co.uk/style-and-beauty/the-return-of-the-brooch-why-estate-jewellery-is-the-quiet-luxury-statement-of-2025/https://www.ethicalconsumer.org/fashion-clothing/what-is-fast-fashion-why-it-problem