Masks: A Lens for Theatre History

The audience sweeps out from you in a sea of dim faces. The light on the stage is blinding, so it’s difficult to see each individual. But you hear them. You hear them after giving a short bow, when their hands come together in a unifying yet chaotic beat as they rise to their feet.

Theatre, as some have remarked, dies a little after each performance. Once acted on stage, it’s history. However, the practice has withstood generations, centuries, and wars.

Theatre history is a broad subject by itself, so much so that it demands a specific kind of attention if one is to trace its origins to the present day.

Masks are a representative feature of theatre. Although today, we may commonly associate them with COVID-19, in the past, they have always been a theatrical matter.

In a timeline of theatre masks, we will follow not only the history of these objects but also the history of theatre.

Ancient Greece

Our first stop is in Ancient Greece. Although it is important to mention that theatre’s origins began before that, even primitive rituals often involved “the seeds of theatre,” as a book calls them.

Dionysus, the god of grapes, may sip his wine contentedly, knowing that the festivals held in celebration of him were a precursor to Greek tragedy, which fed into the Western tradition of theatre. In fact, many of our theatre-associated words are Greek in origin: drama, tragedy, comedy, and theatre, among others.

On the Greek stage were masks for each role. This allowed multiple parts to be performed using a smaller number of actors. Actresses were barred from the stage, a hint that masks were further needed for shows with diverse characters and ages.

Actors wore whole-head masks. The material was stiffened linen, cork, or wood—not very comfortable, I could imagine. Perhaps this was the Greeks’ punishment for excluding the female actor.

The whole-head mask was believed to transform the actor into another person. It has been said that actors, with masks, could become even gods.

Italian Renaissance and Theatre

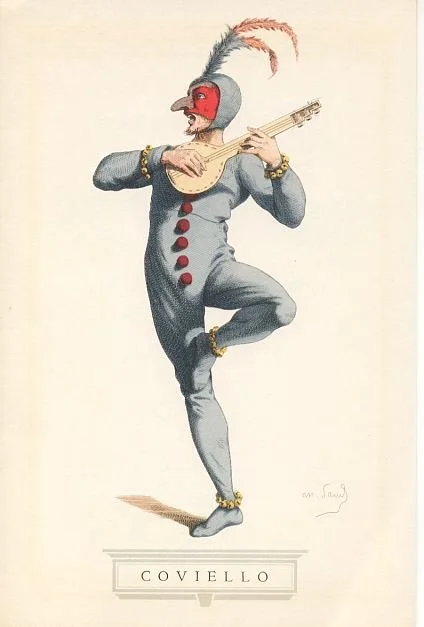

The next prominent period that widely used masks spans the Italian Renaissance in Italian comedy, commedia dell’arte. The commedia dell’arte form was often a professional improv travelling troupe. “Arte” signifies professional, as opposed to amateur, actors. All performers wore masks—except the lovers, whose faces were bare for all to see. Three main actors frequently took the stage: Pantalone, Dottore, and Capitano, who wore distinct masks. The servants, meanwhile, were not portrayed in the prettiest light, literally. A distinguishing feature such as a humped back or an abnormally large nose could take prominence. The point is, with masks, audiences could then identify archetypes in various troupes.

Oriental Theatre

Oriental theatre frequently used and still operates with masks, so it deserves its own attention.

In the Japanese form of Noh drama, the main character, the shite, and his companions wore masks of painted wood. Five types of masks took prominence: monsters, aged, male, female, and gods.

Meanwhile, in Southeast Asia, puppets and masks have frequently been associated with magic and ritual. They still are today. In Indonesia, similar to the Greek supposition that mask-wearers could become gods, it is believed that the mask takes over one’s identity, fully possessing its wearer. If you’re dissatisfied with your personality? Boom! Mask.

In Bali, the huge body mask of Barong performances has been likened to the Chinese lion dance. Two men manipulate the mask, one the head and the other the tail. The anthropomorphized creature is a performance of the fight between good and evil.

A mask is the final card a player pulls in a cast of magic tricks. Who is this character, really? murmurs the audience. From characters to gods, masks remain a transformative component in theatre.

References The Oxford Illustrated History of Theatre (edited by John Russell Brown)The Theatre, An Introduction, Third Edition (by Oscar G. Brockett)